Our big end-of-the-year letter.

The Crown that you *should* be talking about, 'Fashioning the Black Chorus Girl,' a highlight of 'Mexican Fashion,' revisiting the 'Tignon Law' and exploring our mother's closets.

Hello everyone,

This week represents our final newsletter of the year, as our team will be taking time off between December 21st and January 11th for deep restoration following the year we have navigated. From a global and local perspective, it’s been a year of loss, realizations and wins, and so creating a space that houses invaluable, affirming resources like The Fashion and Race Database has been crucial for us to survive and thrive in this “new world” we are living in.

Since we relaunched on July 8th, we have been overwhelmed with support, and I have been able to grow a single-person project into a whole startup. In addition, the database has tripled its amount of educational resources, celebrating and amplifying cultures and communities of people who have been both racialized and minoritized due to historical and present forms of systemic oppression.

That said, The Fashion and Race Database has transformed in various ways–it’s not simply about interrogating the construct of ‘race’ and the insidious nature of racism–it’s about working towards a new way of presenting the history and culture of fashion, beauty and self-expression. It’s about highlighting the limiting notions and vestiges of racial ideologies and correcting mis-representation through our signature, in-house articles that discern harmful appropriation and respectful influence.

I designed each section of The Fashion and Race Database with a clear and (in some regards) radical purpose: to create an educational and supportive platform that applies pressure to outdated and oppressive ways of thinking, and uplifts the stories and histories that need to be told. The database provides a roadmap for change to a tone-deaf fashion industry, offers lessons and resources for educators, students and institutions, and lends an editorial platform for those who believe that it’s time to shift the narrative in fashion.

And we are just getting started.

Reader, I want to acknowledge you for being there for us. You may be a silent subscriber, a donor, an enthusiastic commenter on our Instagram page, or an audience member from our recent conversation series. Whatever it is that you do to support us and this work, we sincerely thank you.

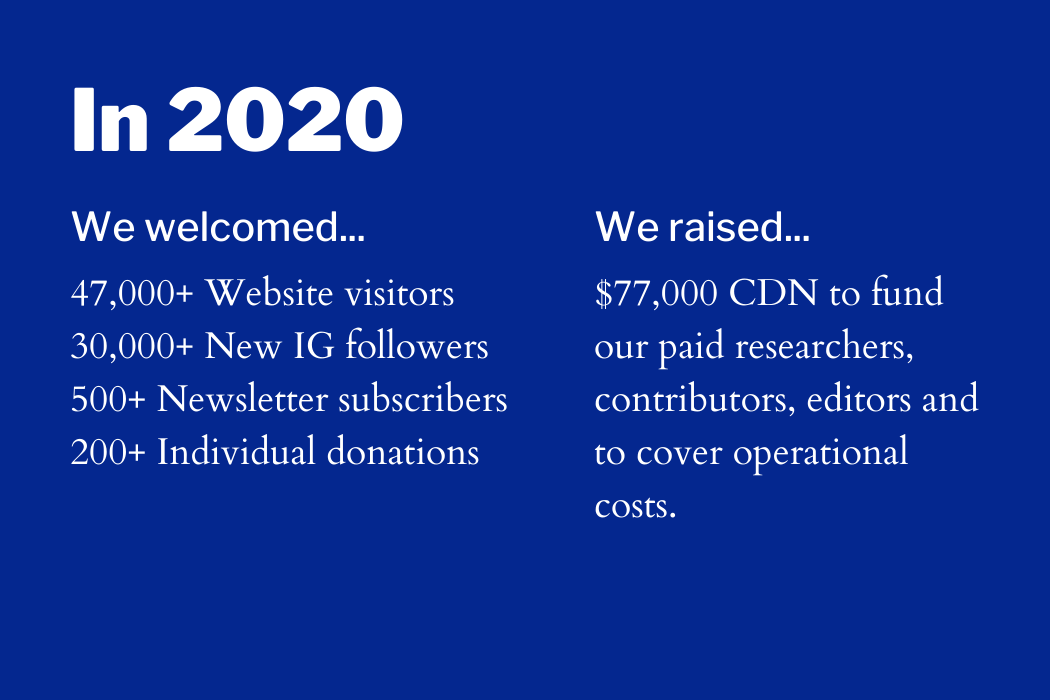

What you helped us accomplish:

So! As we prepare to head into 2021, we are excited about new projects on the horizon and the expansion of our platform. As always, the goal for The Fashion and Race Database is to give you ‘an online platform filled with open-source tools that expand the narrative of fashion history and challenge mis-representation within the fashion system.’

Essay: ‘Ranavalona III: The Last Queen of Madagascar’

Portrait of Ranavalona III in French couture 29 June, 1901.

There’s been renewed interest in the Netflix series, The Crown, in recent months, but more recently, there’s been the notable discovery of a treasure trove pulled by Kerry Taylor Auctions. The UK-based auction house received a court gown amongst numerous, precious objects belonging to Queen Ranavalona III, the last queen of the Kingdom of Madagascar.

The lost archive belonging to the queen sold to the highest bidder–her island's government, ultimately repatriating these relics of fashion history. I’m eager to share with you an excerpt from FRD Research Assistant Kai Marcel’s brilliant essay, 'Ranavalona III: The Last Queen of Madagascar':

As the ex-queen of a French protectorate, Ranavalona occupied an extremely liminal place in French society. She was a woman of color in a majority-white country and a deposed African queen in the center of an empire who conscripted her political downfall, took possession of her ancestral homeland, and effectively kidnapped her and her family. As much as Ranavalona was praised for her style, her sartorial choices were inherently judged on how closely she resembled the Parisienne, an idealized version of French womanhood largely defined by restrictive qualities such as nationalism, whiteness, and constructs of gentility.

You can learn more about this royal figure and the colonialist implications as Kai’s research goes beyond the couture.

From The Library: ‘Mexican Fashion’

This week, FRD Researcher Laura Beltrán-Rubio turns our attention to the history of Mexican fashion. Laura has gathered a selection of sources from our library, offering her own unique perspective as a scholar:

Mexican culture is known worldwide for its rich textile traditions, which reach back over many centuries and predate the Spanish invasion. Fashion in Mexico reveals tensions between what is considered modern and traditional, between local and foreign perspectives. Throughout Mexican history, fashion has played an important role in the search for and performance of national, ethnic, and individual identities.

‘Mexican Rose’ by Tanya Melendez-Escalante (Lectures & Panels)

MeXicana Fashions: Politics, Self-Adornment, and Identity Construction by Aída Hurtado & Norma E. Cantú (Book)

Made in Mexico: The Rebozo in Art, Culture & Fashion by Hilary Simon & Marta Turok (Exhibition)

‘Narratives About Mexico in Fashion Exhibitions’ by Circe Henestrosa & Ana Elena Mallet & Tanya Melendez Escalante (Symposium)

Costumes of Mexico by Chloë Sayer (Book)

José Guadalupe Posada (Mexican, 1851–1913), A woman with her ams open surrounded by figures in elegant dress, ca. 1880–1910. Etching on zinc. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 30.82.111. metmuseum.org.

Essay: ‘Fashioning the Black Chorus Girl’

Es-pranza Humphrey, a historian of Black studies and museum educator, wrote a beautiful essay for us as one of our guest contributors, and her research was led by the following inquiry:

…how did Black chorus girls claim a “Black is beautiful” aesthetic before the phrase even came into the vernacular? Through intellect, through performance, and most importantly, through fashion.

Read her piece, ‘Fashioning the Black Chorus Girl’ to discover both the roots and complexities of Black, feminine aesthetics.

Marion Benda (center) and two showgirls in the Feather Number from the stage production Ziegfeld Follies of 1925, 1925, Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library Digital Collections.

Our Fashion Histories:

'Our Fashion History' shares stories from contributors' photo albums in effort to expand the narrative and visual landscape of fashion history. Here, scholar and guest contributor Dr. Lisette Ordorica Lasater shared with us the sartorial journey of her mother, Juliana (excerpt):

Style has been a way for her to rise above, to be more than just a farmer’s daughter, just another immigrant worker, just another mother. Style allows for her to make her presence known. This simple embroidered cotton dress with a colorful rebozo (shawl) around her shoulders at first gave me pause, and then gave me peace. In this dress, my mother is as content as she was in her taffeta or bridal lace. Here she is fully Juliana: a daughter, a mother, a sister, a grandmother, a comadre (friend).

Photo courtesy of the author.

Another story came to us from curator, writer and researcher Jareh Das, who introduced us to her mother’s impeccable style – including audio snippets.

My mother... was part of this new generation of Modern-Nigerian women who, in the 1960s through to 1970s, celebrated their identity through fashion, reflective of a generation who were bold, confident, experimental and forward-thinking in their sense of dress, knowledge and choice of textiles.

Jareh’s mother wearing Ankara (African wax print fabric) with a friend, Abeokuta Girl’s High School, c.1960s. Photo courtesy of the author.

Objects That Matter: The Tignon

Painting: Jacques Guillaume Lucien Amans. 'Creole in a Red Headdress,' oil on canvas, ca. 1840. Courtesy The Historic New Orleans Collection.

On June 2, 1786, Esteban Rodriguez Miró, the then-governor of Spanish colonial Louisiana, pronounced his 'Bando de buon gobierno'(Edict of good government). He expressed particular concern with the role of free people of African descent in the colony.

...Miró demanded that their hair must be wrapped in a kerchief, citing that 'The distinction which exists in the hair dressing of the colored people, from the others, is necessary for same to subsist, and order the quadroon and negro women, wear feathers, nor curls in their hair, combing same flat or covering it with a handkerchief if it is combed high as was formerly the custom.'

In essence, the edict was an attempted ban on Black elegance, autonomy, and self-fashioning. Any ‘excessive attention to dress’ was considered evidence of misconduct.

Read on as FRD Research Assistant Kai Marcel unwraps the history of an attempted sumptuary law that sought to oppress Black women's stylistic expression.

'Objects That Matter' gathers numerous fashion objects outside of the Western lens and provides a brief history, showing why they matter, as many of these items have been widely appropriated or referenced.

That’s it for now, and I hope you’ve enjoyed our end-of-year roundup of content. We wish you a safe and restorative end to 2020.

Yours in service and solidarity,

Kim Jenkins and The Fashion and Race Database Team: Rachel Kinnard, Daniela Hernandez, Kai Marcel, Laura Beltrán-Rubio

Special thanks to our database alumni and support team members: Adriana Hill, Safia Sheikh, Shanice Wolters, Colleen Siviter